By Crawford Hollingworth & Liz Barker

Behavioural science has contributed much to the understanding of decision-making in the last few decades. We now understand how heuristics and biases can influence our thinking, perceptions, choices and behaviour. Yet, many of the frequently cited studies from behavioural science have been conducted on students, typically in their early twenties.

Consequently, people often ask whether these findings still hold in other generations:

- Does our decision making process differ as we get older?

- Do we become more or less ‘rational’?

- And if minds do differ, how does the 20 year old mind differ to the 70 or 80 year old mind?

Research on the ageing mind by psychologists including Ellen Peters, Laura Carstensen, Mara Mather, Yiwei Chen and Joseph Mikels is still in its infancy, but their initial conclusion is that there are significant differences between the younger and older mind. Analysis of cognitive decision-making in older people finds that key thinking processes change as we age, and that some cognitive biases and heuristics are often more prevalent in older people. Three key differences are outlined below:

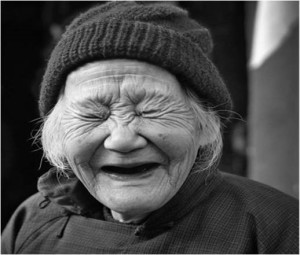

1) The old rely more on System 1 thinking: From our 20s and early 30s onwards, our reasoning and deliberative capacity (known as fluid intelligence) declines with age, and although our knowledge and experience (or crystallised intelligence) increases with age to compensate, eventually this also starts to decline in our 70s, leading to an eventual downward trend in decision-making ability in later years. These cognitive declines are thought to occur due to a reduction in the integrity of brain connectivity; vascular damage in the brain – even in the healthiest of people – reduces the efficiency of white matter connectivity which then affects aspects such as working memory which are crucial for fluid intelligence.[2] Therefore, day-to-day, older people tend to rely less on fluid intelligence and deliberative capacity and more on gut-feel, intuition, rules of thumb and shortcuts (System 1 type decision-making) – things learned through experience and which can actually lead to equally effective decision making in areas they are familiar with. But it’s also harder for them to ignore or sift through irrelevant information and their ability to absorb and process numeric information also declines. For example, when asked which numbers represented the biggest risk of getting a disease, 1 in 10, 1 in 100 or 1 in 1000, 29% of adults aged 65-94 could not answer correctly.[3] Reduced numeracy can mean older people are more prone to framing effects. Ellen Peters, Professor of Psychology at Ohio State University believes that although older people are still capable of drawing on their fluid intelligence and the more deliberative processes of System 2, it takes more effort so they tend to save up precious cognitive resources for important decisions they care about which have significant consequences. 2) Older people are more affected by choice overload: The older we get the more difficult we tend to find it to navigate a proliferation of choice. So older people tend to prefer simple choices with minimal options and information that is succinct and pretty straightforward. An 85 year old retired engineer in the US trying to make her healthcare choices exclaimed: “I’m 85, do I have to go through this nonsense? I’m trying to absorb all the information, but it’s ridiculous. Not just ridiculous, it’s scary. If there was a single card and it was administered by Medicare, and it got the cost of drugs down — wonderful, marvellous.”[4] Research supports this anecdote: 3) Older people are drawn to positive affect more: Affect and emotion play a much larger role in decision-making for older people. They have a greater tendency to focus on, seek out and remember positive emotional experiences and find positive information more salient whilst either not noticing or forgetting negative messages. This may mean they will be more influenced by positive frames than negative. There is also evidence that they are more affected by loss aversion. Much of the research by Laura Carstensen and her colleagues illustrates this phenomenon. For example: Older people’s tendency to focus on the positive is thought to be related to the stage they have reached in life. Gone are the goal striving, purpose-seeking, horizon-expanding days of their youth. Instead they focus on what brings emotional satisfaction, either through meaningful relationships (such as grandchildren or friendships) or ways in which to savour life, because they perceive their life is nearer its end than its beginning – a phenomenon known as Socioemotional Selectivity Theory.[9] Conclusion The insights above highlight two things: In an era where older people are set to become an increasingly significant proportion of society, with different needs and abilities, moving beyond reliance on ageing stereotypes and making use of truly insightful knowledge and understanding will put us in good stead. Notes: [1] This peak and decline in crystallised intelligence may now figure later in life as education levels, health and nutrition improve. A 2015 study at MIT and Harvard by Joshua Hartshorne and Laura Germine found that vocabulary tests revealed a peak in crystallised intelligence in people’s late 60s or even early 70s. The same study also found that peaks in measures of fluid intelligence varied – some peaked early in life whilst others did not peak until age 40. See Hartshorne, Joshua K. & Laura T. Germine. (2015). When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the lifespan. Psychological Science, 26(4), 433-443 and MIT News http://news.mit.edu/2015/brain-peaks-at-different-ages-0306 [2] Logie, R.H., Morris, R.G. “Working memory and Ageing” Psychology Press, 2014, p xiv [3] Peters, E. “Aging-related changes in decision-making” in A. Drolet, N. Schwarz, & C. Yoon (Eds.), The Aging Consumer: Perspectives from Psychology and Economics, (pp 75-101). New York: Routledge; and Peters, E. at RAND 2009: http://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF254.html#agingrelated-changes-in-decision-making [4] Leland J. 73 Options for Medicare Plan Fuel Chaos, Not Prescriptions. The New York Times, May 12, 2004. May 12, 2004. [5] Reed, A.E., Mikels, J., Simon, K. “Older Adults Prefer Less Choice than Younger Adults” Psychology and Aging. 2008 Sep; 23(3): 671–67 [6] Chen, Y. Ma, X., Pethtel, O., “Age Differences in Trade-Off Decisions: Older Adults Prefer Choice Deferral” Psychology and Aging. 2011 June; 26(2): 269–273 [7] Fung H.H., Carstensen L.L. “Sending memorable messages to the old: age differences in preferences and memory for advertisements.” Journal Pers Soc Psychol. 2003 Jul;85(1):163-78. [8] Turk, S., Mather, M., Carstensen, L.L., “Aging and Emotional Memory: The Forgettable Nature of Negative Images for Older Adults” Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2003, Vol. 132, No. 2, 310–324 [9] See the work of Laura Carstensen for more eg Carstensen, L. “A Long Bright Future: An Action Plan for a Lifetime of Happiness, Health, and Financial Security” 2011, PublicAffairs