How I nudged myself to finish the New York marathon, using behavioral economics (and a little help from my friends).

By Álvaro Gaviño

Yes it’s true, it’s not uncommon for people to run these days and many complete the New York marathon (>53,000 last time round). And it’s not uncommon for people to get fit. So let me give you some background so you can give me extra credit for it… In my forties, out of shape, juggling tons of work with three kids, and (let’s be honest) feeling that my top priority for leisure time should be a cold beer.

I wanted to change. I’m sure many of you can identify with that. And like many of you, I knew my track record with earlier plans to exercise and live healthier. My first attempt had been to convince friends to play padel on a regular basis. We even enrolled in an amateur doubles championships. But it didn’t last. The only improvement was in our ever more colorful reasons for not attending matches or friendly training sessions. Second attempt was softball. I have always loved baseball and it was on my before-I-die-to-do-list. But I reckoned death was still some way off and once again, my initial motivation and excitement were soon swamped by the onset of apathy.

So this time had to be different. I conscientiously committed, signed up for the gym, sketched serious plans to live healthier and started to visit a dietician. However, (and here comes the key point of the story), in acknowledgement of my proven potential for falling short, I also signed up for one of those online platforms where you can set your objectives and commit to them. I had read about the way these online sites use behavioral economics, nudging their users leveraging cognitive mechanisms like commitment, social norms, and loss aversion. So now I was going to see whether they could help me reach my goals.

I know the jargon can grate on some ears, but it’s useful, and if you’re not familiar with the concepts underlying these platforms, here’s a quick guide:

Commitment

We individuals want to have a consistent and positive self-image. If we undertake public commitments we’re more likely to follow through to avoid reputational damage. The greater the cost of breaking a commitment, the more effective it is in order to help us counteract our lack of willpower.

This is at the heart of these platforms’ success. You sign up and publicly commit to your goal, whatever it may be. In my case it was going to the gym four days per week. The more people who know what are you are aiming at, the higher your motivation to stick it out until you reach your target.

Social Dynamics

Other human beings shape our actions more than we think… We like to fit in. At times of uncertainty, ‘irrational’ behaviors like non-selfish competition and search for reciprocity, altruism, and fairness can be enhance by group mentality. As such a powerful driver for people’s behavior, social dynamics can be consciously used to nudge people in the right direction. There are many nuances but fundamentally it’s a matter of describing what most people do in a particular situation to influence others to the same path.

These online sites, beyond letting you publish your objectives on your social networks, let you join communities of people making commitments like you, so you are positively influenced to reach your goals.

Loss Aversion

The concept behind loss aversion is that the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. People are more willing to take action to avoid a loss than to make a gain.

This is a really powerful decision-making shaper, which is why in some of these sites you can bet real money against yourself, just so you can feel the loss and therefore to enable you to benefit from the extra motivation. To make it fair you need to have a referee that tells the platform if they should charge you or not. Furthermore, in order to boost its effects, you can ask for your money to be donated to an organization you dislike, what they call an anti-charity. It might be your most hated rival sports club, the National Rifle Association or whatever destination makes you fight the most to avoid them ending up with your hard-earned money. Clever right?

I set a weekly amount that would be taken away from me if a friend didn’t confirm that I was attending the gym. Nothing to lose anyway as I was fully committed this time to carry out my training schedule to the letter.

Nudge

In behavioral economics, Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler introduced this concept in their book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. They described how reinforcements and indirect suggestions work where decisions are being made to positively influence human behavior. The beauty of nudging is that these platforms (and people in general) can use the same biases and heuristics that all too often take us to wrong decisions, but turn them round to help us achieve our goals.

Didn’t Work. I Failed Again.

After a month or so my regularity was flagging. Life reared its ugly head. After all, I wouldn’t be the first or even the last person to sign up for the gym, start in top gear and then just quit, right? Maybe I wouldn’t feel quite so ashamed after all. Actually, when I came to think about it, posting my plans of going to the gym to my social networks didn’t have to have that much impact on my commitment. My online contacts are family and friends. They like me (or they lead me to believe they do) so they wouldn’t take it out on me for quitting the gym. Probably many of them had encountered similar failures of intent, so how could they blame me? Being brutally honest, I wasn’t looking to others in search of clues on what to do. I didn’t feel a pressing need to fit in with the crowd or to help anyone. It was just me, the same old me, going to the gym with a reluctant heart and a couple of posts on social media.

But you already know I finally managed to eat better, lose weight (I lose 15 kilos in just six months), train for the marathon and actually finish it? So what happened?

Think Big

By chance a friend (a real runner) told me he was thinking about doing the NY marathon and the revelation came to me. It was just a matter of scale! I just needed to dramatically increase the effects of commitment, social norms and loss aversion over my decision-making if I was to genuinely boost my motivation and minimize frictions. In fact, as a signed-up behavioral scientist, I could think of adding more mechanisms and apply my knowledge to design my own choice architecture for this matter.

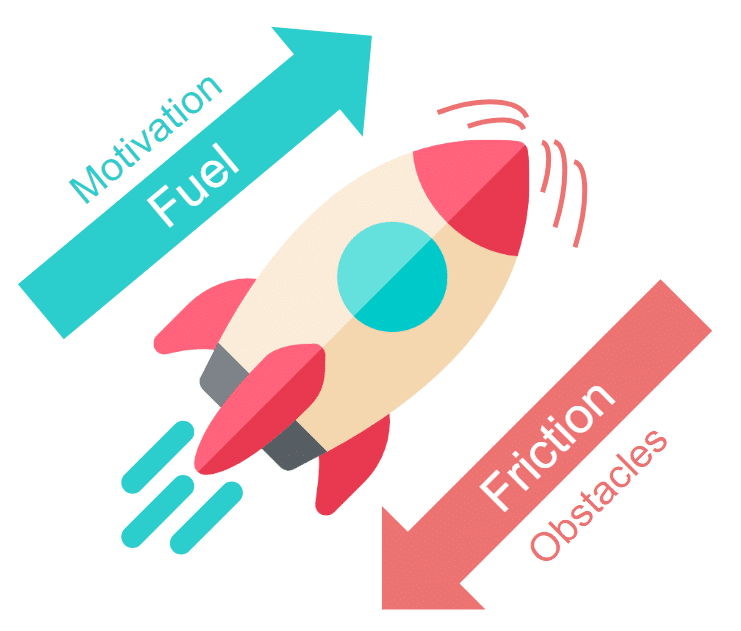

At the last Behavioral Exchange conference in London, Dan Ariely used a nice analogy, picturing our actions as a rocket, with air friction (external obstacles) putting the dampers on the thrust, while the fuel (motivation) drove it forward. I reckoned that in my previous attempts I hadn’t filled up with enough fuel (ie, I failed to care deeply enough) and I hadn’t fine-tuned the aerodynamics to overcome the friction (ie, I ignored known factors such as laziness, familiar patterns, my environment, etc).

All of a sudden, the answer was clear to me, the reluctant exerciser. I had the chance to link together something for which I lacked intrinsic motivation (exercise) to something I looked forward to (traveling). Visiting NY with some of my favorite people in the world was a really attractive plan. So I convinced my wife and another good friend to get involved in this insane idea with me. And on top of that, I had the chance to meet friends that live in the city, some of whom I hadn’t seen for more than twenty years. Not to mention that the challenge of the competition was a reward in itself.

I also reached the conclusion that in my previous attempt I hadn’t properly triggered any of the above-mentioned cognitive mechanisms…

But what if I committed to a real challenge and started telling everyone about my goals in real life. By everyone I mean everyone, whether they were interested or not. Family, friends, team-mates, barely known co-workers and any miscellaneous people I happened to meet. I would enter the elevator at work, like always, but instead of the usual talk about the weather, I would say “You know what? I’m running the NY marathon!” I can hardly describe looks I got. Some assumed I was joking and laughed out loud, others thought I had lost my mind. Although a few politely cheered my absurd optimism, I don’t think any of them believed I would actually manage to do it.

Truth is I still wasn’t too sure myself. But when strangers started their morning elevator ride expectantly asking me how my training was going, my commitment sky-rocketed. All those questions kept the goals very much top-of-mind. I really, really wanted to come back and make them happy by saying “Yes! I finished it”. I had become accountable for the hopes they had pinned on me. Failure started not to be an option so I was finally making use of the Commitment Effect to my benefit.

Traveling to NY was not only attractive but also expensive, so my loss aversion should kick in big time this chance. I acknowledged that the amount of money I’d bet against myself on the platform in the prior attempt hadn’t been enough to make me actually feel the loss as an agonizing pain. But it wasn’t just the euros. As this romantic feeling of pride started to grow in me for what I was planning, no way could I afford to lose that warm sense of doing good.

But I was still doubting so I used two other cognitive factors, called overconfidence and the planning fallacy, in my benefit. The first is the fact that we humans consistently overestimate our capacity to accomplish a job. And the second states that we underestimate the length of time it will take us to complete a task. Often these leads us to make wrong decisions. But this time I kind of conscientiously took advantage of my overconfidence to overcome my initial hesitation. I booked and paid the trip over the (consciously wrong) premises that many people do it, that it’s not that hard, that I had good six months to prepare emphasizing that it’s a lot of time (which is not), that I wouldn’t miss a single training session (which I did) and that I wouldn’t get any injury in the process (I did).

What else did I do? Get as much help as I could and tried to make things as easy for myself as I could. I linked training with people I love and I enjoy being around. The periods I couldn’t run outside because I was injured or because the weather made the running belt or rowing sessions the only option, I gave me the perk of watching my favorite series at the gym. And I wouldn’t watch them any other place so I had another little reason to go. In the meanwhile, we got help from a personal trainer. That made workouts much easier and also loaded a little more weight on the loss aversion side (by the way, he ended up running the marathon with us, but that’s another story).

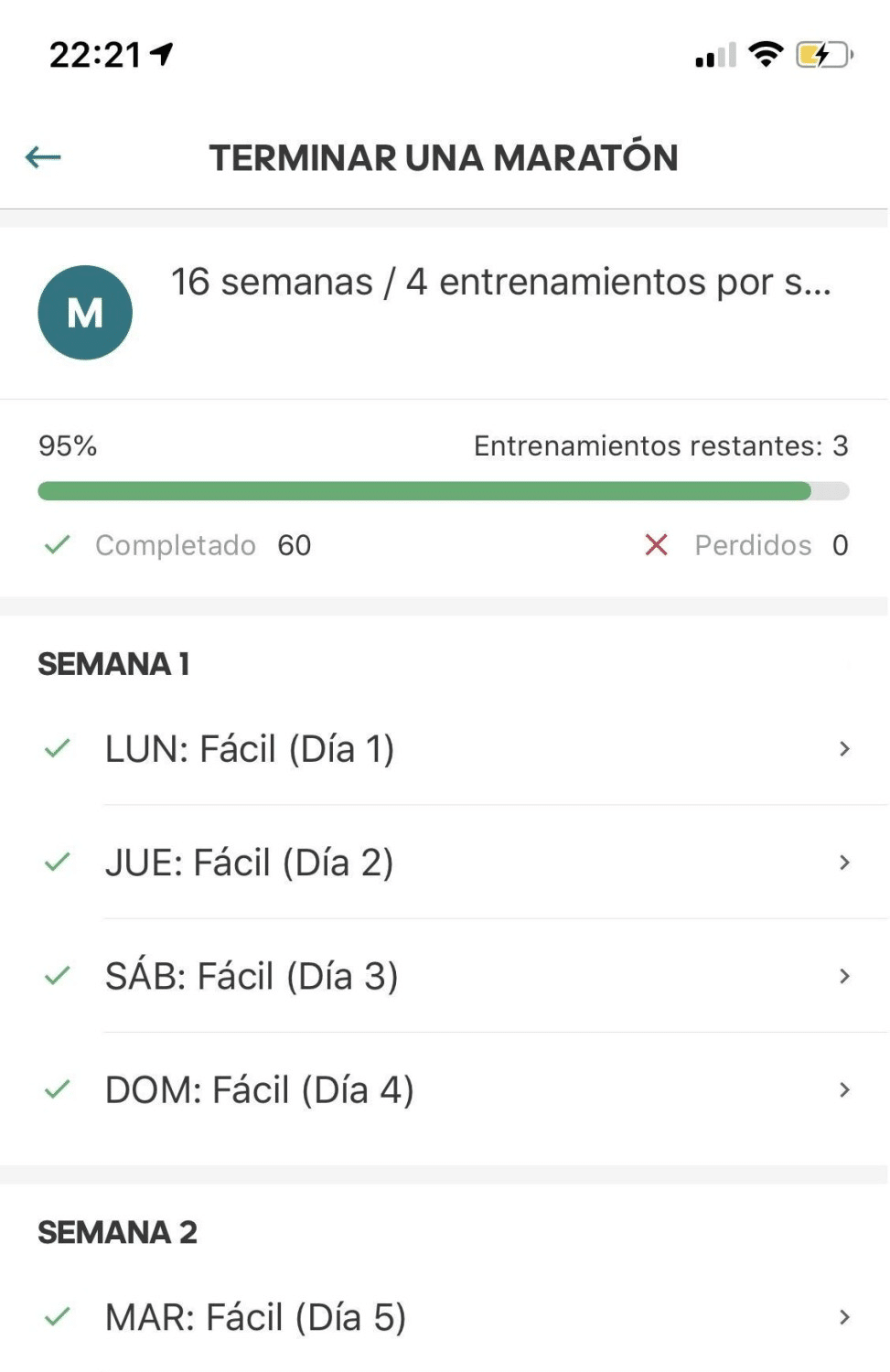

Something that also helped me a lot was using a tracking app to record my running performance. These apply behavioral economics by providing clear instructions and feedback, maximizing the goal gradient effect (knowing how much of a process remains to be completed makes it unambiguous and thus more likely for people to finish it). Mine showed my overall plan status with a simple green progress bar and completed training milestones with a green tick. Soon I was continuously checking that progress bar, willing it to increase the completion percentage. I found myself addictively longing for just a few more of those precious green ticks. If for any reason I missed one I pressured myself to do extra training to recover it.

Don’t get me wrong. It wasn’t easy. I trained till I ached and stuck to a strict diet. In the last two weeks I ran ten kilometers a day, six days out of seven. I also tried to make it as cognitively simple as I could. I started to take decisions in advance so I would do my scheduled training no matter what happened. I refused to let my present-self decide again on a rainy morning to go or not to go for training. No! The decision had already been taken weeks ago! Same with food. I had to make a big effort to choose healthy dishes and it just didn’t come naturally to me… How I love to party!

I Did It!

Yes, I finished what I’d started. For the record, I ran the marathon in 5:04:05. Much better than expected. And not bad for a beginner whose previous record was a five-kilometer race some ten years ago. All in all, I have to say that it’s been one of the best experiences in my life: I have the satisfaction of having achieved an important goal. I am healthier and happier than I was before I started. And I can continue to believe in the merits of behavioral economics.

Of course I’m not arguing that people need to run a marathon to get fit. It’s just what worked for me. Everyone will find their own equivalent of my NY experience. What matters is managing to override lack of motivation and grasp success in whatever it is we want to do. And as a behavioral scientist, I am proud that I proved to myself how the choice architecture of our lives can be tweaked.

To My Fellow Elevator-Travelers and Friends

This article is meant to be about behavioral economics, but well, I’m human too (some would say). And a nice side effect from the commitment approach (remember I started broadcasting my plan to random people in my life?) is that I made new friends, whose help was invaluable to me. Even if many of my fellow elevator-travelers will never know quite how brilliantly they applied behavioral economics, I can tell you, a little nudging goes a long way.