Over the past decade or so the perception around plastic bags has gradually shifted from a tolerated nuisance to a widely discouraged vice. Traditionally, single-use plastic carry bags (SUCBs), commonly made from low-density polyethylene plastic, have been given to customers free of cost when purchasing goods in stores. It comes as no surprise then that the introduction of a mandatory charge of as little as 5 pence per bag in England in October 2015 instigated strong reactions from the consumers at first.

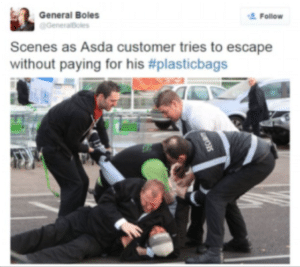

While some thought that they could ignore it …

others developed new, rather innovative strategies to avoid the charge.

(for those curious, this is a ‘bagket’ – a vest jacket with 22 pockets)

In 2014 over 7.6 billion SUCBs were given to customers by major supermarkets in England. That’s something like 140 bags per person. Since the introduction of this scheme, the use of SUCBs has declined by over 80 per cent in England. However, while this policy seems to be a success on paper, there are several unintended consequences that accompany the decline in SUCBs. Seven of the top 10 UK supermarkets increased their plastic footprint in 2019. They sold 1.5 billion “bags for life” last year – roughly 54 per UK household. That’s a bag for a week. These thicker ‘bags for life’ need to be used at least 4 times to have a lower environmental impact than single-use plastic. However, soaring sales of these bags demonstrate that they are now used by many as single-use option, demonstrating the inadequacy of the current policy. Furthermore, a fee can crowd out the emotion of guilt in the consumers for purchasing the plastic bag, thereby reducing their sense of moral responsibility toward the environment.

The good news is that this is a solvable problem. There are alternative policy measures that can be taken to foster a commitment among consumers to reuse carry bags, thereby discouraging the consumption of single-use plastic bags.

What are the alternatives?

Short of everyone adopting a ‘bagket’ (see image 2 above) as daily attire, it is indeed a challenge to ensure that consumers carry their own bag to the store when they go shopping. We need a policy intervention that brings about a behavioural change in consumers to reuse carry bags, and simultaneously keeps their intrinsic motivation to act environment-friendly ways intact.

A study I conducted in 2016 shows that the answer can be found in a simple non-monetary intervention. In a controlled experiment at the London School of Economics (LSE) Behavioural Research Lab, I tested an intervention that targets the framing of the question regarding plastic carrier bags that we encounter at the check-out till. At most grocery stores in England, the question about carrier bags is framed as: “How many plastic bags do you need?”. Framing the question in this manner could imply that taking plastic bags is the norm. This reinforces the very behaviour that the government aims to discourage. I advocate framing the question using a binary yes/no response option, where the ‘yes’ response corresponds with the desired behaviour. Contrary to the original question, the new framing is likely to convey that bringing own carry bag is expected out of the individual. The specific language might also lead to an increased likelihood of participants visualizing themselves doing the activity under consideration, and a resulting increase in the intention to bring their own bag.

A sample of 189 participants completed a grocery shopping task on computer screens and were randomly assigned to the control or one of four treatments. They were informed that five winners would be randomly selected from the participant pool. The winners would get the opportunity to collect their selected grocery items amounting up to £20, from a store on the university campus, free of cost. After adding items to their basket, the participants were presented with the choice of bringing their own carry bag to the store or taking/purchasing a plastic bag. At this stage, the interventions were introduced. The interventions as well as the result of the experiment are explained in the table 1 below. Participants in the control group did not face a charge for the plastic carrier bags and were exposed to the default framing of the question. Treatment 1 had the default framing as well, but along with a charge of 5p. Treatment 2 had the Yes/No framing format and no charge for the bag, while treatment 3 had a combination of the Yes/No format and the 5p charge per bag. Lastly, treatment 4 tests whether interchanging the behaviours corresponding to yes and no response options affects the outcome.

| Charge /No Charge Intervention/ No Intervention | No Charge | 5p Charge |

|---|---|---|

| Default framing | Control Group: “How many plastic bags would you need to carry your shopping? a) None, I will carry my own bag to the store; b) One Bag; c) Two Bags d) Three Bags" | Treatment 1: “Please note that there will be a charge of 5p for every plastic bag that you purchase from the store. How many plastic bags would you need to carry your shopping? a) None, I will carry my own bag to the store; b) One Bag; c) Two Bags; d) Three Bags” |

| % of plastic bag takers | 62.85% | 16.21% |

| Yes/ No framing format | Treatment 2: Will you be bringing your own bag to the store to carry your shopping? a) Yes, I will bring my own bag to the store; b) No, I will need plastic bags from the store”. | Treatment 3: “Please note that there will be a charge of 5p for every plastic bag that is purchased from the store. Will you be bringing your own bag to the store to carry your shopping? a) Yes, I will bring my own bag to the store; b) No, I will need plastic bags from the store” |

| % of plastic bag takers | 17.14% | 5.71% |

| Additional treatment: Variation of the Yes/No framing format | Treatment 4: Yes/No format, but the yes-response does not correspond with the desirable behaviour “Would you need a plastic bag to carry your shopping home?” a) Yes, I’d need a plastic bag from the store; b) No, I’ll be carrying my own bag to the store” | |

| % of plastic bag takers) | 38.18% |

Key Takeaways

It comes without surprise that a combination of the 5p charge and the Yes/No framing format in treatment 3 was the most effective intervention to foster a commitment to reuse carry bags. What is surprising though is that even without the 5p charge, the yes/no response framing intervention in treatment 2 shows nearly the same results as treatment 1, which exposed participants to the default framing of the question along with a 5p charge. Another surprising takeaway is the difference between treatment 2 and 4: the association of ’yes’ with the desired behaviour is remarkably effective, as more than twice as many participants opt for a plastic bag in treatment 4 as in treatment 2.

Crowding out guilt

An analysis of the feelings of guilt reported by participants during the experiment showed that those who opted to purchase a plastic bag for five pence experienced lower levels of guilt on average than participants who chose to take the plastic bags free of charge. This result provides support for the theory that money crowds out emotion (in this case, specifically that of guilt). Further, it is argued that paying money for plastic carry bags can be perceived as a market exchange, potentially leading to the erosion of individuals’ intrinsic motivation to act in environment-friendly ways. Thus, a charge for the plastic bags can crowd out ‘knightly’ or intrinsic motivations. These findings are in line with prominent academic studies that show erosion of intrinsic motivation with the introduction of a monetary intervention.

Conclusion

A simple change in the framing of the question using a binary yes/no response format can nudge individuals to bring their own carry bag to the store, thereby reducing the consumption of SUCBs. Policy-makers as well as privately owned supermarkets can use this evidence towards designing or modifying existing policies for discouraging the single-use of plastic bags. The pandemic has reversed many efforts that were made towards eliminating single-use plastic from the markets, which is why we need to double-up our efforts once the global health crisis ends. As a next step, it would be useful to apply the intervention proposed in this study to a real-world setting and observe its sustained effects over a period of time, which could have a strong bearing on upcoming policy as well as management practices to achieve sustainable development.

This study was carried out by Gauri Chandra as part of her Masters’ Dissertation, under the supervision of Professor Amitav Chakravarti, at the LSE. The full paper can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.9