By Samir Huseynov

How Did the Obesity Pandemic Trigger a New Wave of Policies?

Obesity has been predominantly classified as a national health pandemic affecting the lives of millions. Recent reports alarmingly show that the obesity rate has already passed 35% in seven U.S. states. This health pandemic has dire consequences for individuals with chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular issues, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Reducing the consumed calories has been identified as a plausible non-medical tool to curb the increasing obesity rates.

New York City was the first jurisdiction in the United States to strive to alleviate the obesity pandemic by imposing certain new standards on restaurants and food retailers. In 2008, the city government adopted a new policy demanding restaurants and fast-food chains to visibly display the calorie content of their products in their menus. The officials and policymakers of New York City expected to observe a decline in calorie consumption, relying on the assumption that calorie-informed consumers would cut down their food intake. Later other U.S. states also adopted this new policy initiative hoping to reduce calorie consumption and bring down prevailing obesity rates.

Do Calorie-Labeling Laws Deliver Intended Results?

Since 2011, researchers representing a wide range of disciplines, from public health to economics, have tried to measure the effectiveness of this new policy initiative or Calorie-Labeling laws. However, the answer has become less imprecise as more and more studies emerged robustly scrutinizing this question. The first series of studies analyzing observational data from the jurisdictions that adopted Calorie Labeling Laws reported mixed results. Some articles showed that, indeed, providing calorie information in menus helped reduce the average consumed calories in the states with the new policy initiatives. However, some studies also revealed null effects casting doubts on the effectiveness of the new menu labeling rules. But teasing out a clear causal relationship between the information provision and calorie consumption is very challenging when researchers have to utilize secondary data sources. This technical hardship motivated some scholars to start the second wave of studies trying to document the intended positive consequences of the calorie information provision in controlled experimental settings. Interestingly, experimental studies also revealed mixed results. Some studies documented a robust negative relationship between calorie labeling and consumed calories, while others detected insignificant or null effects.

New Theoretical Economic Models Provide Fresh Perspectives

When my coauthors Marco A. Palma, Ghufran Ahmad, and I started this project, the research landscape was along the lines described above. We had a very ambitious goal—similar to the previous studies—to uncover the true nature of the relationship between calorie information and calorie consumption. However, we also wanted to develop a novel and testable model and experimental design scrutinizing crucial hypotheses of the emerging theoretical economics literature on self-control, temptation, and information.

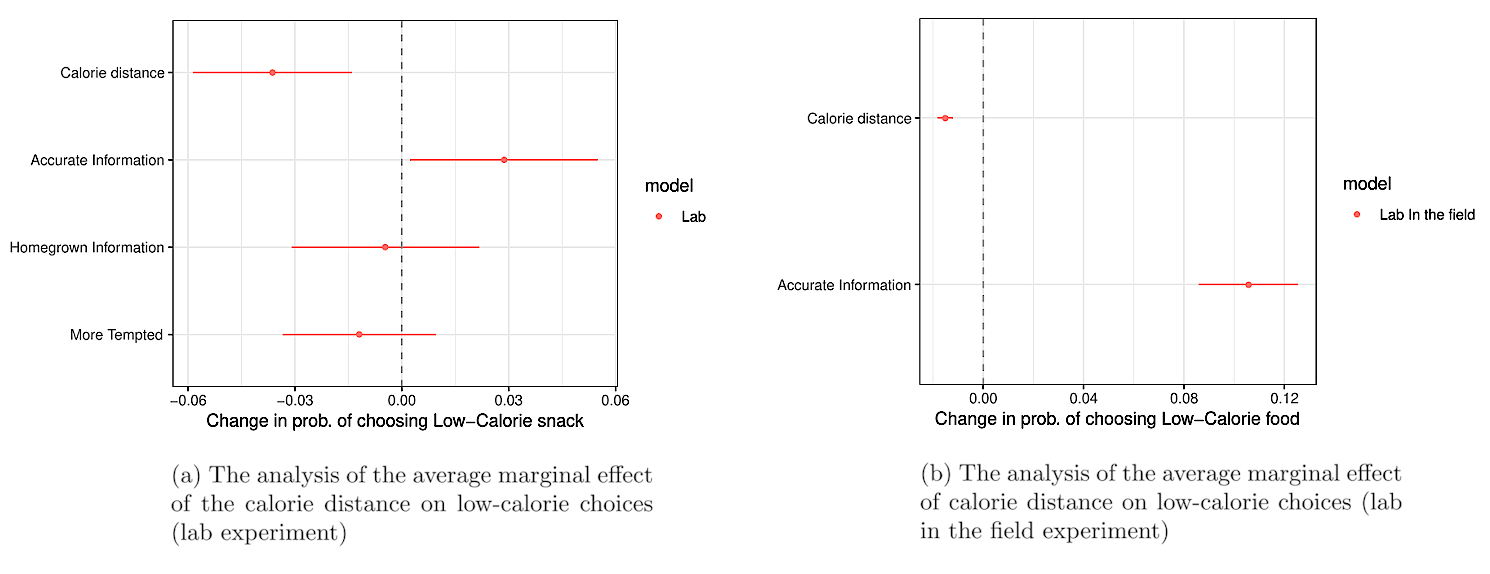

Figure 1: The primary results of lab and lab-in-the-field studies.

Our model predicts that a provision of the calorie information can make the calorie dimension of food alternatives salient and consequently nudge consumers to reduce their calorie intake. Based on the seminal paper of Gul and Pesendorfer (2001), we included an omitted counter-factor (self-control cost and temptation) into our model to explain how calorie information can also be ineffective. Our model hypothesizes that the effect of calorie information on calorie consumption depends on the peculiarities of the food decision environment. The provision of the calorie information can have a non-significant impact on food choices when the high-calorie alternative burdens the decision-maker with an unbearable self-control cost. Explicitly modeling the influence of temptation and self-control costs on calorie information allowed us to bring a new perspective into a growing literature extensively studying Calorie Labeling Laws. Our primary premise was that the policy-predicted positive effect of calorie information on increasing low-calorie food intake could have been neutralized by the adverse effect of menu-dependent temptation urges and self-control costs.

Empirical Findings

We tested our primary hypothesis in the lab and lab-in-the-field studies. Our independent online study showed that there was a positive association between the calorie content of food items and consumer perception about their taste. We proxied temptation urges with the calorie content of food alternatives. In its turn, we modeled menu-dependent self-control costs with the calorie difference of food items on the menu. Our model suggested that decision-makers will feel more intense temptation urges towards high-calorie food items on the menu as the calorie difference between low- and high-calorie food alternatives increases. The increase in the calorie content (hence more delicious and tempting) of the high-calorie food alternative will make choosing low-calorie food items harder, imposing higher self-control costs on the consumer. Our example in the paper clearly depicts this tradeoff:

… an individual choosing a drink from two different menus. Facing a menu with a bottle of water and a zero-calorie soft drink induces a relatively lower temptation tradeoff compared to a menu with a bottle of water and a regular soft drink bottle. The latter imposes a higher self-control cost on the decision-maker since a bottle of regular-soft-drink is more tempting to the average consumer than a zero-calorie soft-drink bottle.

If we plug the calorie information into this scenario, we can expect that informing consumers about the calorie content alternatives will work in the menu with a bottle of water and a zero-calorie soft drink compared to the second menu.

We designed 40 binary menus for the lab study that we conducted recruiting from the student population of a university located in the South-West of the U.S.A. Each menu included low- and high-calorie versions of the same food snack product. This design feature allowed us to control product and brand preferences while focusing on the role of calorie difference between alternatives. Among other treatments, we introduced Accurate Information and No Information treatments to test the impact of the calorie information provision on the proportion of low-calorie choices. Decisions were incentive compatible. At the end of the study, we randomly selected one menu as the binding decision-set, and the subject had to eat their choice to be eligible for the participation reward. We had all products shown in menus available during sessions. We also tested our hypotheses in a lab-in-the-field experiment having subjects to make food choices from binary menus at a restaurant.

Our main results offer a new and reconciling perspective for mixed outcomes of Calorie Labeling literature (see Figure 1). Our studies suggest that providing calorie information is welfare improving and increases the proportion of low-calorie choices. However, its effectiveness greatly depends on menus and menu-dependent temptation feelings and self-control costs. The previous studies do not explicitly model food choice environment and imposed self-control costs. Depending on the relative magnitude of menu-dependent self-control costs and calorie information, calorie provision can have a significant or insignificant impact on food consumption. Therefore, our article suggests considering the specificities of menus while evaluating the effect of Calorie Labeling Laws. The primary practical suggestion of our findings is that choosing a low-calorie food is harder when the alternative is a high-calorie product. Consumers are more likely to reduce their calorie intakes in menus with small calorie differences compared to choice sets with very high-calorie items. So, reducing calories can be successfully managed by choosing which menu you will face before ordering your lunch.

An underlying tenant of behavioral economics is that people do not always act rationally or logically. Though well-intentioned, Calorie Labeling Laws assumes that if consumers receive information, they will make optimal choices based on their long-term welfare. It is no wonder that these laws are producing erratic outcomes because unpredictable and irrational behavior is the essence of human behavior.