By Melina Moleskis

Imagine a single mother in an urban slum, juggling her job, household chores, and the constant pressure of keeping her children fed. Her home is dimly lit, her appliances few and inefficient. Each month, she faces tough choices: pay for electricity, buy food, or save for emergencies. The relentless need to prioritize essential utilities consumes her, leaving little room to plan for the future. What if policymakers could harness this understanding of cognitive scarcity and design energy policies that alleviate this mental and emotional burden?

The Challenge With Energy Poverty…

As governments around the globe race to implement climate policies, the real-world economic impacts are beginning to hit home. And vulnerable communities are feeling the squeeze. One critical challenge that’s forcefully emerging is energy poverty — the struggle of low-income households to meet their basic energy needs.

Why is this happening? Evidence shows that those with lower incomes often face higher energy costs, not because they want to use more, but because of the poor energy efficiency of their homes and vehicles. Many of these people live in older buildings with outdated appliances or drive older cars that guzzle gas. Essentially, those who can least afford it are paying more for energy due to inefficient systems.

…Is That Many People Don’t Apply for the Financial Aid They Are Eligible For

Governments have several tools to fight energy poverty, and the strategies range from short-term relief to long-term fixes. For immediate assistance, direct income support—commonly known as unconditional cash transfers—can help low-income households cover their energy bills. On the other hand, grant funding for building renovations, like installing better insulation or solar panels, offers more lasting solutions by improving energy efficiency.

In the European Union, both of these approaches are set to get a significant boost with the upcoming Social Climate Fund, launching in 2026. However, even with these programs in place, getting people to apply for the funding is often a challenge. Academics and policy-makers agree that there’s a large gap between what’s available and what people actually take advantage of. Simply put, many people don’t apply for the aid they’re eligible for.

Because of Cognitive Scarcity and Its Effects on Decision-Making…

While we often hear about the financial and logistical challenges of tackling energy poverty, there’s another critical piece of the puzzle: the mental load that vulnerable people face. Cognitive scarcity, a concept introduced by behavioral economists Mullainathan and Shafir, helps explain why low-income households, despite being eligible for grants or aid, often fail to apply.

Cognitive scarcity occurs when people facing resource deprivation, like financial insecurity, have reduced mental bandwidth to make well-rounded decisions. Essentially, when you’re worried about making ends meet—whether it’s paying for groceries or paying for rent —your brain becomes consumed with immediate concerns, a tendency known as tunneling. This leaves little capacity for thinking about long-term investments, such as energy-efficient home upgrades, even if those improvements could save money in the future. Research shows that financial hardship often makes people more present-oriented, prioritizing immediate survival over long-term planning.

And it doesn’t stop there. Financial stress also increases cognitive load. Worrying about money makes it harder to focus, stay organized, and follow through on plans. As a result, minor obstacles—like complicated forms, unclear instructions, or long wait times for responses—can feel insurmountable. These so-called “hassle factors” are enough to push many people into procrastination, or even complete inaction, more so when there’s uncertainty about whether the effort will pay off.

In fact, studies suggest that cognitive scarcity is comparable to losing an entire night of sleep, draining mental resources and limiting decision-making abilities.

…Behavioral Science Can Help Ease Energy Poverty

These insights highlight a crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of energy poverty: the behavioral barriers that keep people from accessing help. The problem isn’t just that the programs are there; it’s that for many, navigating them is too overwhelming.

For policymakers, this means that fighting energy poverty requires more than just throwing money at the issue. It’s about simplifying processes, reducing hassle, and providing clear, timely information to ensure vulnerable households aren’t left behind in the green transition. Behavioral science can help with that.

How? A Case Study of Cyprus

In our recent work with Pantelis Solomou, Meltem Ikinci and Theodoros Zachariadis, under the auspices of the Cyprus Institute, we consider the case of Cyprus and the latest grant scheme for energy poverty. Cyprus is an interesting case study because the country’s challenge on energy poverty is significant, with 19% of population recorded as residing in vulnerable households. The low participation rate in past schemes (unofficial information from energy authorities indicates a rate of 45%, leaving more than half of vulnerable households unaided), demonstrates the limited success of traditional policy approaches. As such, the potential benefit from applying behavioral insights within policy-making in Cyprus appears substantial.

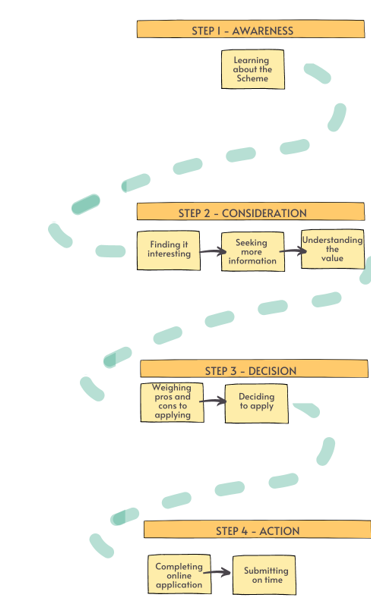

We draw a behavioral journey map by looking at the scheme from the perspective of a vulnerable household, trying to identify the main structural and behavioral barriers present. On this journey, there’s four key steps (Figure 1).

- Awareness involves the decision-maker of the vulnerable household finding out about the scheme.

- Consideration involves finding the scheme interesting and relevant enough to pay attention to it, allocating resources (time, energy, mental bandwidth) for seeking more information, as well as understanding the scheme’s value.

- Decision is about favorably weighing the Scheme’s potential benefits against the hassle required to apply and making the conscious decision to apply.

- Action involves accessing and completing the online application, within the deadline.

FIGURE 1

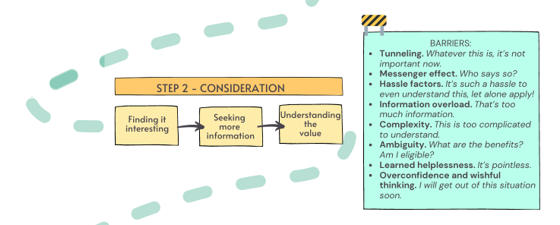

Taken together, these four steps depict the journey of a vulnerable household from before knowing about the Scheme to actually applying to it. But, as expected, within each step, there are various potential obstacles, both structural and behavioral. For instance, for Consideration, the decision-maker is up against a number of barriers (Figure 2), including:

- Tunneling, causing them to focus on immediate concerns and neglecting needs that are further away in the future.

- The presence of hassle factors, like public servants not answering phonelines and website links leading to generic homepages, signal an unsupportive environment, discouraging citizens from choosing to seek more information.

- Information overload from bundling instructions for all households with that for vulnerable households, and including EU regulations and national targets.

FIGURE 2

What can policy-makers do? Some practical recommendations that emerge from behavioral science studies can help overcome these barriers. For instance, replacing monologue-style presentations with discussion sessions within relatively small, newly created groups among the targeted population, has been shown to help reshape social norms and alleviate the stigma associated with participating in such schemes, thereby increasing positive word-of-mouth.

To help with tunneling and capturing people’s attention, policy-makers can try tapping into loss aversion by framing the cost of not participating in the Scheme with clear examples of future savings. For example, ‘If you live in a 100 sq.m. residence, every month you go without solar panels costs you X money’. This is likely to be much more effective than its mirror message ‘If you live in a 100 sq.m. residence, you can save X money every month with solar panels.’ Another good strategy is tapping onto the power of social proof and in-group identity, by communicating examples of people who have already applied to the scheme, carefully selecting those who bear similarities to the targeted population, such as the problems they face and village they live in.

While hassle factors cannot be fully eliminated, where possible, it’s worth making seemingly minor changes that make it easier and less uncertain for an individual to apply. A practical, low-cost solution that has worked in alleviating information overload is a “passport page” that provides an executive summary with the key points that would interest the intended audience. Moreover, assisting vulnerable households with the initial steps of the application process (e.g., by pre-filling or pre-populating some information) has also proven to go a long way in helping people fill out application forms.

Conclusion

If there’s two things to take away from this work, those would be that, one, simply bombarding people with information is rarely enough to lead to action – especially so for people (temporarily) affected by a scarcity mindset. And two, while the obstacles present in such processes can be either structural (how the grant scheme is designed and implemented, like hassle factors) or behavioral (how people with a scarcity mindset decide, like tunneling), both categories of obstacles share two things in common. First, they are often missed or ignored by policy-makers. Second, overcoming these obstacles involves small, cost-effective structural changes – as opposed to the difficult process of behavioral change. In other words, by recognizing the way vulnerable households decide, it’s possible to make small adjustments to existing policy processes to attain much better results and help fight energy poverty successfully, on the way to a just, green transition.

This article was edited by Lachezar Ivanov.