By Gerald Smith

Each of us makes hundreds of routine decisions every day—usually following intuitive and predictable decision “rules,” such as choosing to not buy milk or meat too near the expiration date. Such behavior on the part of buyers is well documented in behavioral economics—where it is termed risk aversion—and it seems rational. However, when we engage in price-setting, we adopt an entirely different orientation with surprisingly counterintuitive behaviors that contradict what traditional economists might have predicted. We oversimplify our decision making, we fall back on familiar price-decision rules, and we often consistently set prices lower than they rationally should be.

Prospect Theory and Price-Setting

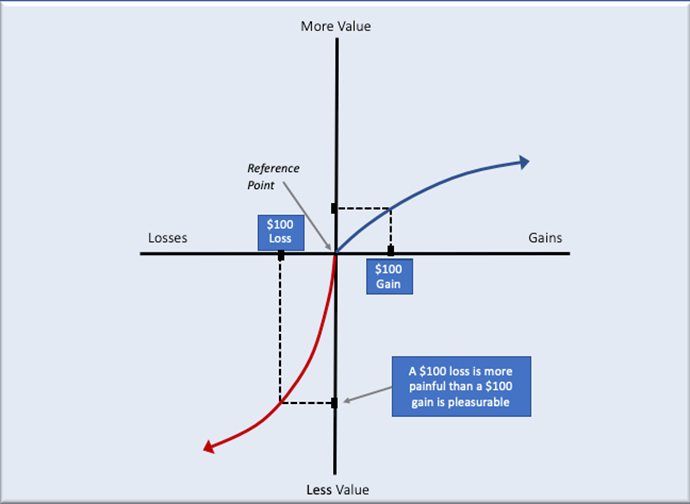

One of the most important behavioral advances of the last century is Prospect Theory, proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. In recognition of the impact of this and related work, Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002; Tversky had passed away just six years earlier. According to Prospect Theory people use a reference point to frame prospective alternatives as either potential gains or losses, and judge how much pleasure is associated with gains, or pain is associated with losses. When people consider prospective gains, they usually make risk-averse decisions; they prefer certain gains that may be smaller, rather than risk uncertain gains that may be larger (see figure). When people consider prospective losses, they usually make risk-prone decisions; they prefer to risk the possibility of larger but uncertain losses rather than smaller but certain losses. Have you ever postponed making a dental or medical appointment when encountering a surprise medical symptom for fear of a negative prognosis, even though your situation may become worse by delaying? In order to avert an immediate loss, you are actually willing to accept even greater risk.

Prospect Theory: “risk averse for potential gains, risk seeking for potential losses”. Adapted from: Kahneman and Tversky (1979); Rothschild (2015) https://jtbd.info/getting-consumers-to-switch-to-your-solution-fa292bb29cea.

While testing Prospect Theory in price-setting, pricing researchers at Notre Dame and Ohio State universities made important framing discoveries about how managers frame the task of price-setting. As a baseline for comparison, they gave a sample of students and retailers the classic Kahneman and Tversky Prospect Theory gamble, shown below (the bracketed data was not shown to respondents):

Would you choose

Option A offering an 80% chance of getting $4,000 and 20% chance of getting $0? [An expected value of $3,200.]

Or, would you choose

Option B offering $3,000 for sure? [An expected value of $3,000.]

Chances are, you were probably risk averse and chose the sure Option B rather than the more valuable but risky Option A, consistent with Prospect Theory. Indeed, the researchers reported that 79% of respondents chose Option B, the sure outcome, and 21% chose Option A, the risky option.

However, preferences reversed when the problem was reframed as a pricing problem. Here study participants were told that “Your firm is considering a price decrease for your commodity product in the coming period. In the current period, unit price is $8.00, unit cost is $5.00, and sales are 1000 units.”

Would you choose

Option A: Cut price to $7.40 with an 80% chance that you’ll sell 1,400 units (a 40% gain) and a 20% chance that you’ll sell 1,000 units (no gain)? [Expected value of $3,168.]

Or, would you choose

Option B: Maintain price at $8.00 with a 100% certainty that you’ll sell 1,000 units (no gain)? [Expected value of $3,000.]

Chances are, you were probably risk prone and chose to cut price, the risky Option A, rather than maintain price, the sure Option B, contradicting Prospect Theory (even though the expected values of the outcomes are roughly the same as the Prospect Theory gamble, shown above). The researchers reported that 87% of respondents chose Option A, the risky price cut, while only 13% chose Option B, the sure outcome by maintaining price. In a related study comparing cutting price to raising price (with manufacturing managers involved in their firm’s pricing decisions), the researchers reported that 78% chose the risky price cut option rather than the sure option of maintaining price. For the price increase, only 45% chose the risky price increase option, and 55% chose the sure option of maintaining price. The bottom line: when it comes to price-cutting, price-setters seem to behave with capricious rationality. Price-cutting seems in league with addictive risk-seeking behaviors like sky diving, rock climbing, gambling, recreational drug use, or promiscuous sexual activity. Like gamblers riveted to a game of chance, they consistently choose to cut price with a chance for a risky gain—risk proneness; but they avoid raising price to avoid the chance of a risky loss—risk aversion.

Price-Setting Biases and Distortions of Prospect Theory

What’s going on? When making pricing decisions, managers frame price-setting outcomes not in terms of profits or value outcomes, but in terms of customers and sales to customers—contradicting Prospect Theory. One retailer who chose to cut price said: “I believe it is sometimes wise to cut [price] to help increase the possibility of new customers.” Another said, “You must gain customers at all times, that is your purpose.” The researchers concluded: “The potential gain of customers and the opportunity loss of not gaining customers [produces] risk-seeking in a price cut context,” and the potential loss of customers produces risk aversion in a price increase context. Some managers in the study were encouraged to literally calculate the outcomes of the price-setting choices before them. “Many of those who did calculate the profit implications were [still] willing to cut price in the interest of gaining customers, even when the expected profit value of the price cut was lower than that of holding price.” Citing this research, the Harvard Business Review concluded: “This and many other studies indicate that pricing managers routinely set prices too low, sapping their companies’ profits.” This is a seminal finding: Unlike typical economic decision-making that focuses on the expected value of profit outcomes, price-setters reframe pricing decisions in terms of expected customer sales gains, or losses, a bias that persistently undermines pricing profitability.

In theory, price-setting is expected to be an activity that requires slow, effortful analytic calculations. However, for many it is more of a behavioral memory-based task involving heuristic mental shortcuts. For example, with Kahneman and Tversky’s availability heuristic, people tend to use information that is easily recalled from memory, that may be recent, or frequently observed, or dramatic. With price-setting, the default information that often seems to remain top-of-mind—and therefore most influential—is that of customers and sales to customer (sales volume, or revenue). Changes in sales offer vivid, and often memorable, evidence to price-setters of the outcomes of their price-setting decisions. “[Sales] volume shifts can be a very vivid indicator of performance to business decision makers. An increase in store traffic, for example, is a much more concrete, immediate, and available indicator of success than profit (which is more abstract and often a lagged measure of success) . . . particularly in the small business context,” concluded the researchers.

Used strategically and thoughtfully, price-setting can generate profits, increase customer price satisfaction, and increase employee morale with more stable and rational pricing. But mistaking pricing’s purpose to justify persistent price discounting trains customers, sales persons, and price-setters to repeatedly and irrationally manipulate price.