By Carly Robinson

Many different organizations and sectors use awards to motivate positive behaviors. Presumably this practice of granting awards is so widespread because it seems like common sense: recognizing effort and performance with an award will send a message to recipients that they are doing a great job and should keep up the good work.

Schools, in particular, often employ elaborate systems of honors and awards to motivate students, ranging from gold stars and pizza parties to honor rolls. One increasingly common practice among educators is to incentivize students with awards for excellent attendance. My research team (comprised of Jana Gallus at UCLA, Monica Lee at Stanford University, and Todd Rogers at the Harvard Kennedy School) and I realized that, despite their widespread use, we know very little about the effectiveness of attendance awards.

We conducted a randomized controlled experiment involving 15,329 middle and high school students in California to test what happens when you offer students symbolic awards for excellent attendance. We also wanted to know if the way in which schools offer the award matters. That is, are attendance awards more effective when they are announced, and students have a goal to work for (i.e., a prospective award)? Or are attendance awards more effective when they are given after the fact, indicating that students have been doing a good job and that they should keep it up (i.e., a retrospective award)?

We randomly assigned the students in our sample – all of whom had at least one perfect month of attendance in the Fall semester – to one of three groups:

- A control group, that received no additional communications and did not learn about an attendance award.

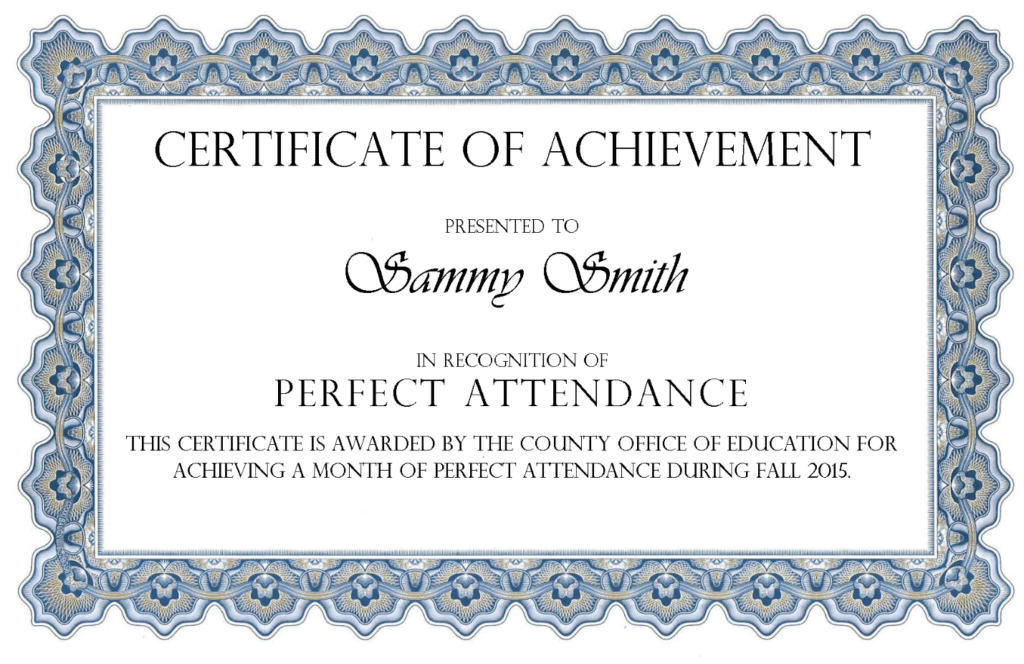

- A prospective award group, that received a letter in January telling them they could earn an award if they had perfect attendance in February (the letter included a picture of the certificate they would receive).

- A retrospective award group, that received a letter in January notifying them that they had earned an award for having a perfect month of attendance in Fall, along with the actual certificate.

We expected that students in both award groups would have fewer absences in February, the subsequent month, than students in the group – and we publicly posted our predictions.

Findings

As the title suggests, the results were not what we expected. Students in the retrospective award group who earned an award for a previous month’s attendance missed more school in February than those in the control group – the award increased absences by eight percent. Those in the prospective award group who were offered the opportunity to earn an award if they had zero absences in February showed no reduction in absences relative to those in the control group. But when we looked at these students’ absences in March, after the award period was over, they too attended fewer days of school than students who were never offered the award.

A follow up survey experiment shed light on what might have happened. The awards may have unintentionally signaled to students that they had attended school more than their peers, and more than their schools had expected them to attend. By implying that students had overshot some target level of attendance, the awards may have caused students to feel licensed to attend school less.

Implications

Educators continue to hand out attendance awards because they think they work – we surveyed educators and only two percent correctly predicted that retrospective awards might increase absenteeism. But we find that offering students awards to improve attendance is, at best, ineffective and can even be demotivating. These findings suggest we need to think more critically about the unintended signals awards may be sending to recipients.

Perhaps more importantly, this study highlights the need to evaluate the effectiveness of even the most well-established practices. There are many practices, both in and beyond education, that are accepted because they seem like common sense. But we found that the ubiquitous practice of giving attendance awards – that almost everyone thought worked – actually does not work. By leveraging the science of human behavior, we can both challenge widespread practices and identify new strategies to motivate positive behaviors.