By Marc Oliver Rieger

Should I Decide or Wait?

Good decisions require information, but ultimately there is a tradeoff: neither rushed decision making without a solid basis nor eternal procrastination with costly, but inefficient information search are ideal. Many previous studies have found, however, that humans mostly tend to fall into the second trap: they keep collecting information when the existing one is already sufficient. In our study (conducted jointly with Mei Wang, WHU and Otto Beisheim School of Management, and Daniel Hausmann, University of Zurich), we wanted to shed some light into this and determine the reasons for this “overpurchasing” of information.

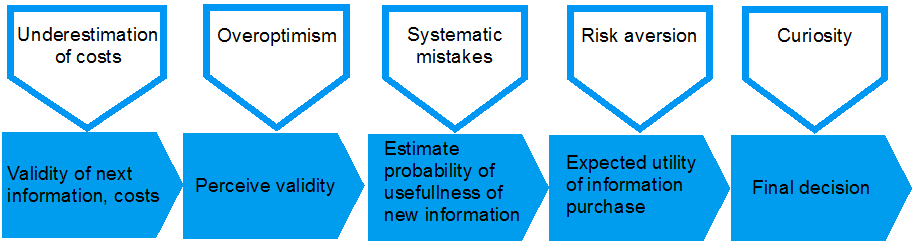

A priori there are at least five potential explanations for this effect:

- We might underestimate the costs of the information search.

- We might be overoptimistic about the probability that additional information is correct.

- We might be too risk averse to take an early decision.

- We might simply be curious to know more.

- Finally, we might make systematic mistakes while condensing the collected information.

But which of these explanations are the right ones?

Decisions in an Experiment

To figure out the true causes of overpurchasing, we designed an experiment that allows us to disentangle the different explanations. The experiment confronts the subjects with a straightforward decision task where they have two options: either deciding between two alternatives A and B based on some already existing information or collecting more information. The information is always clear (“Alternative A is better” or “Alternative B is better”), but only correct with a certain probability. In the standard setting this probability is known.

Let us look at some example task:

We have already some information and it tells us that alternative A is better. The information, however, is only correct with 70% probability. We can decide now (i.e. choose A) or we can collect two more pieces of information, each correct with 80% probability. If we decide correctly, we earn some money (say $1000), but information is also costly, so if we collect more information we need to pay $100. Should we collect the additional information or directly choose A?

Compared to a benchmark decision that optimizes the expected return, we found a substantial amount of overpurchasing of information. Since our decision task was very simple and clear (as compared to real life decisions), we already see that overpurchasing is not only caused by the complexity of a decision task.

We also included decision problems where the probability of the information to be correct was not exactly known to the subject, e.g., it was stated as “between 60% and 80%”. Moreover, we also asked our subjects different questions, e.g., how likely they estimate their decision to be correct if they went on to collect information.

Combining the results from the various tasks, we can then one by one exclude possible explanations for overpurchasing (see Figure):

- Underestimation of the costs for the information search cannot be a reason, as in our experiment the costs were clearly stated.

- Being overoptimistic about the probability that additional information is correct would only lead to overpurchasing when probabilities are not precisely known, but we did not find this effect.

- Risk aversion does also not explain overpurchasing. (We can exclude this with another part of our experiment, that uses a somewhat nifty method explained in our paper.)

- We also excluded curiosity as a reason for overpurchasing: we gave subjects the chance to acquire the additional information for a much cheaper rate if they decide before seeing it, but they nearly never chose that option.

- This left the final explanation: systematic mistakes when condensing the collected information. Indeed, we find that the estimated probability to be successful after collecting more information is much higher than the actual probability.

Figure: Various factors that may lead to a final decision that overpurchases information.

In summary, we found that overpurchasing seems to be mainly the result of a systematic bias when estimating the gain from acquiring additional information. A person simply thinks he or she will have a much more solid foundation for a decision after collecting additional information, even though it turns out that the gain is only marginal. In some situations, we even found overpurchasing when the additional information did not help at all, because it had a low validity and so even if both additional pieces of information contradicted the first one, the best choice was still to follow the first (much more reliable) information.

What Can We Learn From This?

The key message to take away is that we should really think twice about postponing decisions. How likely is it that additional information is actually going to make a difference? Waiting for a better decision is often the worse decision!

Knowing that we tend to overestimate the impact of additional information can be important to help us avoid the costs of a slow decision. It can also help us avoid the costs of unnecessary, but expensive information: Maybe we don’t need an expensive consulting company to advise us on a decision that won’t get much clearer afterwards? Maybe deciding based on what we know (instead of spending time on making a marginally better decision) gives us a competitive edge over a slower competitor?

Might there be other reasons why overpurchasing of information occurs in real life? Yes, of course. In real life, for example, there are also principal agent problems: maybe costly external advice is not needed to aid in the decision process, but to blame somebody else in case of an unlucky outcome? This was not supported by our experiment, which showed that overpurchasing of information also occurs when there is no “blame game” involved and people are deciding without ulterior motifs. It seems to be in our nature to overestimate the effect of additional information, and once you are aware of that, you can avoid it and make braver and better choices!